Like other Western colonial-settler experiments, for over 70 years, Zionists have been systematically erasing the culture and history of indigenous Palestinians to justify their forced removal and the theft of their land. Ilan Pappe, in his book The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, calls this ‘memorocide’ and in The Palestine Nakba, Nur Masalha elaborates,

“The founding myths of Israel have dictated the conceptual removal of Palestinians before, during and after their physical removal in 1948… The de-Arabisation of Palestine, the erasure of Palestinian history and the elimination of the Palestinian’s collective memory by the Israeli state are no less violent than the ethnic cleansing of the Palestinians in 1948 and the destruction of historic Palestine.”

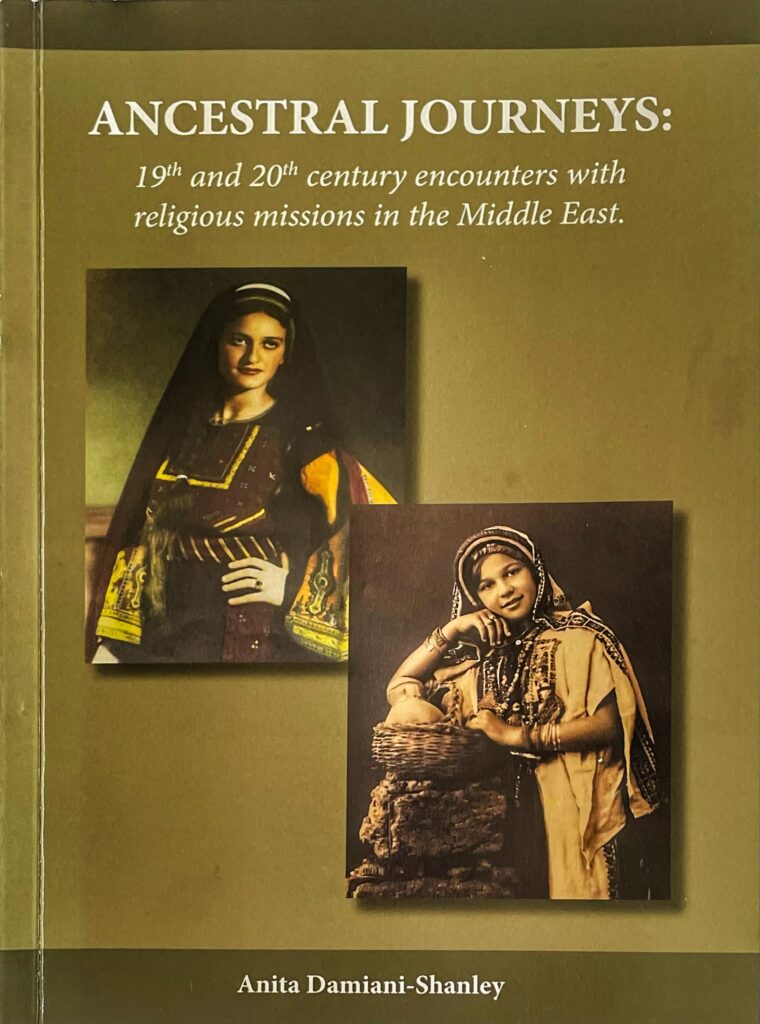

This is why books such as Ancestral Journeys and Western Missions are so vital in recording the memories and eyewitness accounts of Arabs and Palestinians who experienced the arrival of Western colonialists to the Middle East, were co-opted into their wars, witnessed the rise of Zionism and then became refugees in the Palestinian Nakba. Anita Damiani-Shanley’s book will most certainly help perpetuate their heritage and rightful historic claim to Palestine.

Ancestral Journeys is however much more than the story of two families, one Arab and the other Scottish joined in marriage. It traces the influence of missionaries, archaeologists, traders and colonialists competing with each other for a share of the Near East as the Ottoman Empire met its demise. Richly illuminated with family photos, the three main chapters trace the ancestral journeys of Damiani-Shanley’s extended family from Scotland and Lebanon to Iraq and then to Palestine. A fourth chapter traces the role of the Anglican Church in Palestine.

An important strand of Damiani-Shanley’s book records how Presbyterian, Congregational, Church of Scotland, Episcopal, Anglican and Quaker missionaries were sent to the Near East, how they interacted with Arab culture, values and beliefs, with the indigenous churches, and with Jews and Muslims. Three main missional approaches emerge – evangelistic, social and political.

The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) was one of the first American Christian missionary organizations, founded in 1810, to send missionaries to the Near East. Henry Jessop describes the approach of ABCFM missionaries. “Let us print and teach and live before them a Christian life and we may win them to Christ. The Arabic Bible with educational and medical missions will be the efficient factors in bringing Islam to Christ.” (p. 59).

Others were more interested in what they could learn about the Bible from the indigenous people of the Near East. William Thomson, for example, a missionary who travelled widely in the Near East studying the manners and customs of the populations of Syria and Palestine believed, “that the Bible could only be fully and clearly understood by understanding its Oriental origin and the context in which it was written.” He was convinced that the behaviour of the local inhabitants might very well reflect that of their biblical ancestors (p. 62).

Damiani-Shanley highlights the strategic role played by missionaries in education and training, especially for women, founding orphanages, schools, teacher training colleges, universities, clinics and hospitals right across the Near East. For example, “The joint efforts of British and American missionaries were greatly responsible for laying the educational foundation of Lebanon…” (p. 22)

In this regard, the American University Beirut (AUB) was one of the most strategic and innovative. Bayard Dodge, President of AUB from 1923-1948, wrote that the University was established and run on the basis that “education should relate to its surroundings” and that “when suitable persons could be obtained, the native Arab element should be introduced as fast as possible into the professorship… On that basis the region’s qualified teachers could be drawn into the academic workforce.” (p. 52)

This same philosophy was applied in Iraq when the Somerville family moved to Baghdad, where, under the British Mandate, James was appointed a school’s inspector with responsibility for teacher training and refresher courses. Many of the Iraqis subsequently recruited into the educational system were graduates of AUB in Beirut (p. 77)

In the chapter on Palestine, however, the author paints a more complex and controversial motive for mission. She points out, for example, how in the 19th Century, the French and Russian missions “were viewed as representative of their countries’ political power in the Ottoman empire.” (p. 91). Over the same period but especially following the Balfour Declaration and granting of the British Mandate, this was true of Anglican missions also.

“It is important to realise early on the ulterior motives that lay behind some of the educational and political establishments. On the one hand they helped develop the youth of the Palestinian indigenous nation, but on the other hand most of them were following a religious and political agenda…The British Mandate was set up to provide a shadow government for the establishment of a Zionist state… They totally repressed any signs of resistance from the local Palestinians… They created districts for the Jews and others for the Arabs.” (pp. 92, 100)

She laments how in her experience, most Protestant missionaries “have continued to turn a blind eye to the political and religious basic rights of the Palestinians. The true history of the region continues to be viewed through the telescope of myth, colonialism and twisted images of quasi political-religious rights.” (p. 97).

The early British missions in Palestine, the Church Mission Society (CMS) and London Jews Society (now known as the Churches Ministry Among Jewish People (CMJ) are criticised for showing little or no interest in the needs of the majority Muslim population.

“Rather, both the CMS’ and the LJS’ presence in Palestine was devoted to specifically evangelical Protestant concerns – anti-Catholicism in the case of CMS and a new interest in worldwide Jewry in the case of LJS. These early missionaries’ ignorance of Islam was almost total, to the point that Islam featured only as a vague evil in their reports and mission statements, against their specific, theologically determined interest in opposing Catholicism and converting the Jews.” (p. 101)

She adds, “Here again, the British understood their presence in Palestine not in relation to Palestine’s inhabitants but in relation to contemporary Christian theological debates and Great Power politics.” (p. 102).

In the second half of the 19th Century, under the leadership of Bishop Samuel Gobat, Anglican mission focussed on education opening 42 schools, orphanages and clinics, and ordaining two Palestinian priests. Nevertheless, in the light of the ease with which the Zionists took over from the British Mandate, Damiani-Shanley asks,

“Did the British affiliated schools set out to fulfil educationally the political requirements of the Mandate? How much were their aims and objectives directed towards an increased Jewish presence in Palestine?” (p. 104)

Referring to the missional approach of the LJS/CMJ, she writes, “Obviously this mission was working against Palestinian interest and would have no connection with the local Arab Anglican churches” (p. 107).

And of CMS missionaries, she writes, “Although Palestinians … welcomed the excellent education offered in CMS schools, with often highly dedicated teachers, they, in the final analysis, played an essential role in the Mandate government’s agenda.” (p. 136)

In a final chapter the author reviews the contribution made by successive Anglican Bishops in Jerusalem between 1825-1960. While emphasizing the significance of the Anglican schools and hospitals, as well as appointment of indigenous leaders, she laments that “In this mandated country, a colonial, imperial mentality and a fascination with Jewish teachings, was uppermost in their minds as they ruled the country.” (p. 163).

Little it seems has changed in 200 years. She observes, “American and European nations have continued to focus on the area’s resources and its strategic position in the world. Their close military, ideologic and religious association with Israel, together with the economic rewards to their countries of being able to acquire oil in large amounts at low prices, keeps their armies and politicians in these areas. Religion continues to be used in Palestine/Israel to achieve political and expansionist aims.” (p. 187)

Herein lies the importance of books like Ancestral Journeys and Western Missions, for it is “not just a way of remembering the past, but one of understanding the present, and also as a way of entering into the future.” (p. 163).

At a grassroots level, there is growing awareness of, and support for, the indigenous Palestinian Christian community in Europe and America, not least due to the advocacy work of networks such as Sabeel and Kairos in Palestine (Sabeel-Kairos in the UK). However, our church leaders like our politicians, seem more concerned to placate the Zionist Lobby than respond to the Cry for Hope from the leaders of the Palestinian Church which is now close to extinction.

I very much hope Anita Damiani-Shanley’s book, and others like it, succeeds in changing this destructive mentality and furthers the gospel work of bringing justice, peace and reconciliation to Palestine/Israel and the wider Middle East.

Ancestral Journeys may be purchased from Hadeel, A Fair Trade Palestinia Crafts, Books and Food Retailer and Wholesaler, 123 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 4JN