Did you realise that once broadcast, TV signals begin an endless journey outward into the cosmos at the speed of light? That means our earliest TV broadcasts are probably travelling through star systems more than 400 trillion miles from earth. Do you realise that our neighbours living 60 light years away are watching the first episodes of the Lone Ranger in black and white. 50 light years away they are now watching Bonanza. 40 light years away they have moved on to the original Star Trek series. 30 light years away they are able to watch the Dukes of Hazzard. Just 20 light years away it’s the Sopranos. Those only 10 light years away are being blessed by countless episodes of Lost. Scientists tell us that the further away your neighbours live, the more likely they are to hold outdated, inaccurate and stereotypical views of you.

Did you realise that once broadcast, TV signals begin an endless journey outward into the cosmos at the speed of light? That means our earliest TV broadcasts are probably travelling through star systems more than 400 trillion miles from earth. Do you realise that our neighbours living 60 light years away are watching the first episodes of the Lone Ranger in black and white. 50 light years away they are now watching Bonanza. 40 light years away they have moved on to the original Star Trek series. 30 light years away they are able to watch the Dukes of Hazzard. Just 20 light years away it’s the Sopranos. Those only 10 light years away are being blessed by countless episodes of Lost. Scientists tell us that the further away your neighbours live, the more likely they are to hold outdated, inaccurate and stereotypical views of you.

Does it worry you what your neighbours think about you? What impression do you give them? Is it accurate or a distortion? When they see you coming, are they welcoming or do they lock the door and hide? Does it matter what impression you give? What about the people next door? Over the road? Down the street?

The people you meet every day on the train? The people you work with? It may have been questions like this that prompted a certain lawyer to ask Jesus the question,

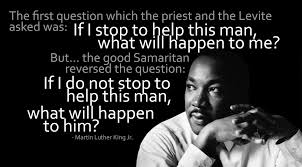

“who is my neighbour?” meaning, “who do I bear some responsibility for and who can I ignore?” We answer this question all the time whether we consciously think about it or not. We answer this question by the way we treat other people. In reply to the lawyers question, Jesus told a story, a parable. A parable is simply a story with a kick in the tail, a story in which we find ourselves an active if unwitting participant rather than an objective observer or innocent passerby. This parable of Jesus is as topical and controversial today as it was to those who first heard him. Jesus’ audience would have been very familiar with news of hapless victims, robbed or murdered on that very road. Even today the road from Jerusalem down to Jericho isn’t the kind of place to take the family on a Sunday afternoon picnic. So Jesus had their attention. Christ talked about violence and danger – and we certainly have plenty of that today. He talked about crime, racial discrimination, fear and hatred. In this parable we also see neglect and concern, we see love and mercy. We know very well what the parable says, but what does it mean?

Let’s spend a few moments considering the characters involved in this story and their attitudes toward the man travelling from Jerusalem to Jericho.

1. To The Thieves: He was a Victim to Exploit

The thieves did not see a fellow human being made in the image of God. They saw someone they could exploit. It did not matter what happened to him, as long as they got what they wanted. Their philosophy was “What’s yours is mine-I’ll take it”. God gave us things to use and people to love. We live in a culture that has got it round the other way. Jesus Christ never exploited a person. We must beware of looking at people and thinking “what can he do for me?” We may not mug people to steal their money, but we can so easily hurt people with our words and actions. To the thieves this man was a victim to exploit.

2. To The Priest: He was a Nuisance to Avoid

Jericho was a priestly city, a place where many of the priestly families lived. It is the oldest continuously inhabited city in the world. It has a warm mild climate all year. By comparison, Jerusalem is cold and exposed in winter. So Jericho was the place to live, and Priests and Levites would regularly frequent this road on their way to and from the Temple.

Jericho was a priestly city, a place where many of the priestly families lived. It is the oldest continuously inhabited city in the world. It has a warm mild climate all year. By comparison, Jerusalem is cold and exposed in winter. So Jericho was the place to live, and Priests and Levites would regularly frequent this road on their way to and from the Temple.

Of all people one would have expected them to help this poor man. Priests were drawn from the upper class of society. They constituted the privileged elite of Jewish society. The Priests rode. The poor walked. So what excuses might the priest have offered had he been caught on a security camera travelling by on the other side? “I’ve got to remain pure in order to serve God”

When confronted by a stripped and unconscious person the priest faced a dilemma. How could he help someone who might be a sinner? His religious laws forbade him go within four metres of a dead person in case he became defiled. Then he wouldn’t be able to perform his duties.

His peers would have applauded him for not stopping so that he could perform the higher work for God. Perhaps he thought, “It’s not my problem”. Maybe it was. Why didn’t the religious leaders do something about the dangerous road? Cain asked, “Am I my brother’s keeper?

The answer is “Yes, regardless of your sister or brother’s race or colour.” Perhaps he was afraid of an ambush. May be it was, maybe it wasn’t. What mattered was the person in need. If we allow fear to determine our actions we will be paralyzed from serving God. Maybe he thought “Let somebody else do it” The priest could have said,

“the Levite coming up behind me, he can stop, I don’t need to.” But then the Levite could then have thought, “The priest didn’t do anything, so why should I?”You and I can always find somebody to point to as an excuse for our own neglect. Failure to act when we should is just as sinful as to act when we shouldn’t. If we go through life wanting our own way, then other people will always be a nuisance because they will get in our way. But if we go through life with our eyes open seeking opportunities to share the love of Christ, then every nuisance, every delay, every distraction, every encounter with another person becomes a divine appointment, an opportunity to serve God.

To the robbers this man was a victim to exploit.

To the priest and Levite he was a nuisance to avoid.

3. To The Lawyer: He was a Problem to Discuss

Jesus told the story in reply to a lawyer’s question.

The lawyer was an expert in religious law. Israel lived under religious law in a similar way as Sharia law is imposed in some countries with a Muslim majority. He was then a professional theologian. The lawyer wanted to test Jesus on a point of law. To win an argument. Jesus turns the conversation round to teach a fundamental truth about concrete action. The lawyer was safe with theories,

“who is my neighbour?” He was threatened with the reply, “What would you have done in this story? What kind of neighbour are you?” To the robbers this man was a victim to exploit. To the priest and Levite he was a nuisance to avoid. To the Lawyer: He was a problem to discuss.

Contrary to their expectation, Jesus elevates a despised Samaritan, as the one who did not permit racial or religious barriers to hinder him from helping this stranger.

4. To The Samaritan: He was a Neighbour to Love

The Samaritan did not blame the injured person for the collective attitudes of either race, and use that as an excuse for doing nothing. He dared to act as a concerned individual, in three specific ways.

He Showed Compassion

“But a Samaritan, as he travelled, came where the man was; and when he saw him, he took pity on him.” (Luke 10:33)

This word has with it the connotation of being deeply moved inside. It is the word used to describe the way the Lord feels about lost sinners. Compassion describes the way God feels about us. When we show compassion we are merely demonstrating our family likeness. He showed compassion.

He Took the Initiative

“He went to him and bandaged his wounds, pouring on oil and wine. Then he put the man on his own donkey, brought him to an inn and took care of him.” (Luke 10:34)

The Samaritan could have excused himself. He was a foreigner in a hostile country. He was alone and vulnerable, but God’s love does not look for excuses.

It does not ask why, but why not? The Samaritan cleansed the victims wounds with wine and soothed them with oil. He bound up the wounds so they would begin to heal.

He took the man to the inn to recover and promised to return to pay the bill. The lawyer was willing to talk, the Samaritan was willing to act. He demonstrated compassion. He took the initiative and, thirdly

He Bore the Cost

“The next day he took out two silver coins and gave them to the innkeeper. ‘Look after him,’ he said, ‘and when I return, I will reimburse you for any extra expense you may have.’” (Luke 10:35)

He interrupted his schedule to help this man. It may have made him late for a business appointment, it may have delayed him from seeing his family. But he bore the cost. What did he have to gain from this personally? Nothing – except the joy and strength that come when you do God’s will. When you serve in love without expecting recognition or reward. What did the Samaritan show? Compassion, initiative, sacrifice. So what is the point of the story?

Why did Jesus tell this story? Why did Jesus tell this story in this particular way? What was it in Jesus story that challenged his hearers? Because we have not yet got to the heart of the story yet… The key to understanding the parable is in the wounded traveller’s condition. It is not a curious incidental. Jesus says he was unconscious and naked. These details are skilfully woven into the story to create the tension that is at the heart of the drama. The Middle Eastern world was made up of various ethnic-religious communities. You could identify a stranger coming toward you in two ways. By their accent and their clothing. In the 1stCentury the various ethnic communities within Palestine used an amazing array of dialects and languages. In addition to Hebrew, one could find settled communities using Aramaic, Greek, Samaritan, Phoenician, Arabic, Nabatean, and Latin. Not without reason was the north known as the Galilee of the Gentiles. No one travelling a major highway in Palestine could be sure that the stranger he might meet would be a fellow Jew. But a short greeting would reveal their language if their clothing had not already given away their nationality. But what of the man in this story? Jesus said,

“They stripped him of his clothes, beat him and went away, leaving him half dead.”(Luke 10:30).

Jesus tells us he is stripped of his outer clothes and is unconscious. Why did Jesus add these details to the story? What was the condition of the victim? Naked and unconscious. Jesus reduced the victim to the status of…. A human being! Created in the image and likeness of God, That is the point of the story. That was the dilemma for Jesus hearers and everyone who has heard the story since. Because they couldn’t tell if the victim was one of their community or a stranger, a foreigner. The question is will you stop for a human being, not one of us or one of them. The lawyer tried to trick Jesus. He wanted Jesus to draw a line in the sand. To say whom were his neighbours and whom were not. But Jesus turned the question round and asked

“Which of these three do you think was a neighbour to the man who fell into the hands of robbers?”(Luke 10:36).

Not a ‘good’ neighbour, just a neighbour. When Jesus asked the lawyer which of the three was a neighbour, the lawyer could not even bring himself to say the word “Samaritan”. He was still resisting Jesus attempt to reach his heart. I wonder whether we have got the message? Perhaps we too need to ask the question “What kind of neighbour are you?” “What kind of neighbour are you to anyone you meet?” For Jesus teaches that we cannot separate our relationship with God from our responsibility toward those he brings across our path. The lawyer wanted Jesus to define the limits of his responsibility. He wanted Jesus to identify those he had to be a neighbour to and those he could ignore. Jesus turned the question round. The question is not ‘to whom need I be a neighbour?’ But rather ‘what kind of neighbour am I?’ – to anyone I meet? I invite you to join a revolution this week. Break the spiral of fear and hate in our community with acts of compassion and mercy – especially toward those who are different, those who are the outsiders, those who are the strangers. Who ever the Lord brings across your path today. Your assignment from Jesus this week is really very simple: “Go and do likewise.” (Luke 10:37). Lets pray.

A homily given at the Annual Open Day of the Living Stones of the Holy Land Trust, Saturday 16 November 2019.