This book seeks to explain how many of the problems of the Middle East in the last century can be traced back to the colonial ambitions of Britain and France and in particular to the ‘venomous rivalry’ between them in their struggle for mastery of the region. It was this rivalry which lay behind the Sykes-Picot agreement, the Balfour Declaration, the creation by Britain of the kingdoms in Iraq and Transjordan, Britain’s support for the independence of Syria and Lebanon, and French support for the Jewish underground which was working against the British in Palestine in 1948.

This book seeks to explain how many of the problems of the Middle East in the last century can be traced back to the colonial ambitions of Britain and France and in particular to the ‘venomous rivalry’ between them in their struggle for mastery of the region. It was this rivalry which lay behind the Sykes-Picot agreement, the Balfour Declaration, the creation by Britain of the kingdoms in Iraq and Transjordan, Britain’s support for the independence of Syria and Lebanon, and French support for the Jewish underground which was working against the British in Palestine in 1948.

What follows is a summary of the main themes of the book, combined with quotations from key passages.

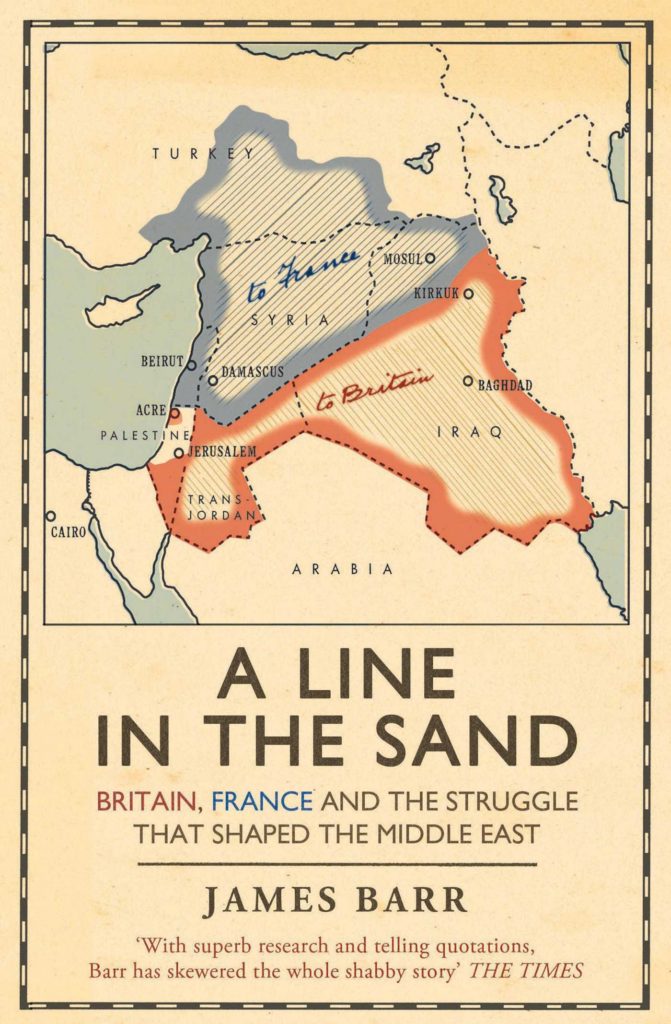

The Sykes-Picot agreement (May 1916) was an attempt by Britain and France to deal with their rival ambitions in the Middle East and to define spheres of influence in the region after the fall of the Ottoman Empire. The ‘line in the sand’, which was literally drawn on the map by Mark Sykes (for Britain) and Francois Georges-Picot (for France), ran (in Sykes’ words) ‘from the “e” in Acre to the last “k” in Kirkuk’. Lebanon, Syria and northern Iraq (including Mosul) were allocated to France, while Transjordan and southern Iraq were allocated to Britain. Because Britain and France both wanted control of Palestine, it was finally agreed that it should come under international control.

‘The compromise, which neither power liked, was that the Holy Land should have an international administration.’ (2)

‘For the time being the agreement was kept secret, a reflection of the fact that, even by the standards of the time, it was a shamelessly self-interested pact, reached well after the point when a growing number of people had started to blame empire-building for the present war.’ (32)‘… as far as the British were concerned, the Sykes-Picot agreement had been an academic exercise to resolve an argument, not a blueprint for the future government of the region.’(36)

The British were unhappy with the Sykes-Picot agreement for two reasons:

(1) they wanted to keep France out of Palestine and control it themselves; and

(2) they wanted to control Mosul for access to its oil.

It was in this context that Britain in November 1917 declared its support for the Zionist movement through the Balfour Declaration. It did so for four main reasons:

(1) to frustrate the French and keep them out of Palestine;

(2) to ensure British control of Palestine in order to protect the Suez Canal;

(3) to win the support of Jews worldwide (but especially in E. Europe and the USA); and

(4) to draw the USA into the War.

Most histories have concentrated on the second, third and fourth of these reasons; but the distinctive contribution of this book is that it explains the importance of the rivalry between Britain and France and Britain’s determination to keep France out of Palestine.

[The Balfour Declaration was intended] ‘both to trump the French and to improve relations with the Zionists’ (33).

‘… the British urgently needed a new basis for their claim to half the Middle East. Already in control of Egypt, they quickly realised that, by publicly supporting Zionist aspirations to make Palestine a Jewish state, they could secure the exposed east flank of the Suez Canal while dodging the accusations that they were land-grabbing. What seemed at the time to be an ingenious way to outmanoeuvre France has had devastating repercussions ever since.’(2)

‘In 1878 Britain seized Cyprus and, four years later, Egypt and the Suez Canal in order to secure the route to India. As the canal turned into the major artery for Britain’s growing eastern commerce, Egypt became the fulcrum of the British Empire.’ (9)

(Concerning David Lloyd George’s decision to launch the invasion of Palestine in 1917). ‘Well aware that such a move would certainly spark accusations of imperialism, he decided that support for the stateless Zionists’ aspirations was a good way to thwart French ambitions in the Middle East and silence [President Woodrow] Wilson. Unlike the Sykes-Picot agreement, sponsoring the Zionists looked high-minded, but the prime minister’s reasoning for doing so was unchanged. As Asquith put it, sourly but accurately, “Lloyd George … does not care a damn for the Jews or their past or their future, but thinks it would be an outrage to let the Christian Holy Places – Bethlehem, Mount of Olives, Jerusalem etc – pass into the possession of “Agnostic, Atheistic France”!’ (35)

The US President, Woodrow Wilson, was very critical of European imperialism, and at the Versailles Peace Conference in 1917 spoke strongly in favour of self-determination for the Arabs. Under the terms of the Mandate, Britain and France were committed to prepare Palestine and Syria for independence; but because of their own imperial interests, had little intention of doing so.

‘So far the United States had been reluctant to join the Allies’ side. As public opposition to imperialism grew stronger, late in 1916 the newly elected US President, Woodrow Wilson, urged all the belligerents to renounce the imperial ambitions that he believed were largely responsible for the war. His challenge elicited a disingenuous response from the British and French governments, in which they described themselves as “fighting not for selfish interests but, above all, to safeguard the independence of peoples, right, and humanity.” They even said that they were committed to “the setting free of the populations subject to the bloody tyranny of the Turks.” The bespectacled, high-minded Wilson as yet knew nothing of the Sykes-Picot agreement, but all the same regarded this sudden conversion with the scepticism that it deserved. “No nation should seek to extend its polity over any other nation or people,’ he repeated in January 1917; “every people should be left free to determine its own policy … the little along with the great and the powerful.” This was the doctrine that became known as “self-determination”.’ (33-4)

The French wanted to hold Britain to what it had agreed in the Sykes-Picot agreement, while the British wanted to control Palestine and wanted control of the oil in Mosul. The capture of Damascus by Arab forces (under the leadership of T.E. Lawrence) created facts on the ground which Britain hoped would enable the Arabs to control Damascus and thus keep the French out and make it impossible to implement this part of the Sykes-Picot agreement. T.E. Lawrence played a decisive role in these developments and was always aware of the duplicity of the Sykes-Picot agreement and the Balfour Declaration and of the way Britain had broken its promises to the Arabs.

– Lawrence was angry that, when Britain wanted to attack the Ottomans in order to weaken the Germans, it was largely because of pressure from France that Churchill decided against an attack on Alexandretta (on the border between Turkey and Syria) and instead ordered the attack on Gallipoli between April 1915 and January 1916, which proved to be a major disaster.

– It wasn’t until May 1917 that he learned the details of the Sykes-Picot agreement from Sykes himself and realised ‘their profound implications’.

(In a note to his chief) ‘Clayton: I’ve decided to go off alone to Damascus hoping to get killed along the way … We are calling them [the Arabs] to fight for us on a lie and I can’t stand it.’ (46)

– One of the reasons he was so keen to lead the Arab forces right up to Damascus was that he wanted to prevent France from gaining control of Syria. He had realised that France wanted to support the Arabs only to ensure that they did not succeed, since a successful Arab revolt would threaten France’s power and influence. Having understood France’s real motives, Lawrence was able to persuade the British authorities in Cairo and London to supply weapons to help the Arab Revolt. This material support helped to turn the tide of the Revolt after early defeats, and enabled them to begin their advance northwards.

– When Lawrence met General Allenby, who was leading the allied forces in Palestine, he proposed that, in order to support the allied attack on the Ottoman forces in Palestine, he would lead the Arabs in an attack east of the Jordan at the same time. After Allenby’s successful attack on Beersheba and Gaza in October, the Balfour Declaration was published in order to prevent Palestine coming under international control after the end of the war. Lawrence had not been aware of the plan for the publication of the Balfour Declaration.

‘To ward off the inevitable French pressure for an international administration once Palestine had been conquered, the British government now made its support for Zionism public.’

(56)- When Lawrence and the Arab forces reached Damascus, the contradictory promises Britain had made to the Arabs and the French became obvious.

‘With the Arabs laying claim to Damascus by right of conquest, the British would now be forced to admit that they had promised the city not just to them but also to the French.’ (62)

– When explaining to Churchill after the war why he had turned down the offer of a knighthood, he said it was ‘the only way he could make the king realise that “the honour of Great Britain was at stake in the faithful treatment of the Arabs and that their betrayal to the Syrian demands of France would be an indelible blot on our history”.’ (117)

– In 1921 Churchill, now in charge of the Colonial Office, enlisted Lawrence to work on Palestine and Mesopotamia. Churchill saw this as an opportunity to neutralise Lawrence, while Lawrence saw it as an opportunity ‘to reverse the failure that had depressed him throughout 1920.’

At the Cairo Conference (13-20 March 1920), Churchill decided that placing Abdullah on the throne in Transjordan and his brother Faisal on the throne in Baghdad would be ‘the best and cheapest solution’. It would do two things at the same time: (1) demonstrate ‘unilateral support for self-determination’, and (2) ‘achieve the British goal of dominance in the Middle East obliquely’ (70). Britain had to accept that France would control Syria, and had to reckon with French hostility to its schemes, which were seen by France as against their interests

‘As the choreography suggested, the enthronement of the Arab Faisal was initially of mainly symbolic importance. But in the Middle East it was an important departure, and it poisoned relations between Britain and France. As the French had feared it would, Britain’s decision to promote a man whom they had just kicked out of Syria quickly raised Arab hopes of self-government elsewhere.’ (126-7)

France’s aim in creating Lebanon and dividing Syria was largely to protect its own interests and suppress Arab ambitions for independence.

‘After Gouraud [France’s High Commissioner in Syria] had seized Damascus [for the French] in 1920, his secretary de Caix bluntly set out the options open to the general. France could either “build a Syrian nation which does not yet exist … by smoothing out the deep rifts which still divide it,” he suggested, or “cultivate and maintain all the phenomena, requiring our arbitration, that these divisions give [us]. I must say that only the second option interests me.” Gouraud agreed. In August 1920 he hived off Lebanon in a bid to curry favour with the significant Christian population there, and carved up Syria into four separate provinces that divided Damascus and Aleppo and recognised the minority Alawite and Druze sects.

‘Gouraud cast the move as an acknowledgement of the country’s religious and ethnic differences, but it was immediately recognised for what it truly was: a cynical attempt to split the nationalists that was also directly contradictory to the mandate, which required France to prepare Syria and Lebanon for self-government.’ (129-30)

Both Britain and France as colonial powers faced strong resistance from their Arab subjects, and both used violent tactics to suppress protests. They refused to help each other to face opposition from their Arab subjects.

(By 1921) ‘… French rule in Syrian and Lebanon appeared increasingly arbitrary, confessional, exploitative and corrupt.’ (129)’

‘The British and the French blamed one another’s policies for the opposition they each began to face. Each refused to help the other address the violent Arab opposition because they knew that they would only make themselves more unpopular by doing so. For almost two years in the 1920s, the British ignored frequent French requests to stop the rebels who were fighting their forces inside Syria from using neighbouring, British-controlled, Transjordan as a base. The French in turn shrugged when the British asked them to clamp down on the Arabs who were taking sanctuary in Syria and Lebanon during their insurgency in Palestine in the second half of the 1930s. Lacking neighbourly support, both France and Britain resorted to violent tactics to crush protest that only enraged the Arabs further.’ (2-3)

(During the revolt against British rule in Iraq) ‘Infamously, Churchill even authorised the Royal Air Force to investigate the use of mustard gas against “recalcitrant natives”. Although the Air Force wisely did not, by the end of the revolt over 8,400 Arabs would be dead. So too were almost 2,300 British soldiers.’ (113)

(The British vice-consul in Damascus writing after the brutal suppression of the Druze Revolt by the French in Syria in 1926-7). ‘It is difficult to see how the Mandatory authorities, after all the hatred and bitterness which they have stirred up, can for many years find any responsible Syrians to collaborate whole-heartedly with them in the task of governing the country’. (139-40)

(A British policeman in Palestine writing about British methods in suppressing the Arab Revolt in Palestine, 1936-39). ‘It got to the stage the so-called terrorism became critical and in order to fight terrorism, we became terrorists more or less.’ (185)

As early as 1920, Britain was aware of the problems it had created for itself in Palestine.

‘The British realised … that they had burdened themselves with an insoluble problem. “The problem of Palestine,” wrote Britain’s most senior general, “[was] the same as the problem of Ireland, namely, two peoples living in a small country hating each other like hell.” Nor were the Jews showing the gratitude the British expected of them. When the director of military intelligence visited Palestine soon after the riots, it dawned on him that there was no reason to suppose that the Zionists and British would ever be “really friendly”. The friendship would “only last as long as the Zionist State were dependent on Great Britain for military protection”, he realised. This was an insight that would prove acute.’ (101)

Gertrude Bell was not at first supportive of independence for the Arabs in Mesopotamia, but later changed her approach and was acutely aware of Britain’s unwillingness to keep its promises to the Arabs.

‘Bell had previously agreed … that the Arabs were neither capable of, nor interested in, governing themselves… But Bell then changed her mind when she experienced what was, quite literally, a Damascene conversion on her way back from Paris to Baghdad. When she too met the nationalist leaders in Damascus, she was astonished by the power the Bahgdadi faction wielded and the extent of their ambitions. She warned London that there was “no way of keeping the people of Mesopotamia in the path of peace but by giving them something which they won’t willingly abandon. Good government, by someone else, e.g. by us, isn’t enough.”’ (105)

‘… when in March 1920 the General Syrian Congress declared Faisal and Abdullah the heads of Syria and Mesopotamia respectively, there was no Arab government in place in Baghdad, nor was there any sign that one was imminent. “Well we are in for it,” Bell wrote when she heard the news from Damascus. “We shall need every scrap of personal influence … to keep this country [Mesopotamia] from falling into chaos.” Her optimism that her own influence might still work was utterly misplaced because, by then, the British had run out of credit with the Iraqis. As she later admitted, “We didn’t show any signs of an intention to fulfil our promises; as far as the local administration was concerned we didn’t intend to fulfil them if we could possibly help it.”’ (p 107)

After the collapse of France in 1940, Britain played a significant role in defeating the Vichy government in Syria, supporting the Free French and promoting independence for Syria and Lebanon. Britain’s main aim in doing so was to reduce France’s power and influence and to reduce Arab anger over British policies in Palestine.

‘The fall of France in 1940, and the subsequent decision by the French in the Levant to back the Vichy government, ended both sides’ reluctance to interfere in one another’s problems. In June 1941 British and Free French forces invaded Syria and Lebanon to stop the Vichy administration providing Germany with a springboard for an offensive against Suez. After the Vichy French surrendered a month later, the British government entrusted the government of Lebanon and Syria to the Free French. When that move caused Arab anger British officials decided that the best way to divert attention away from Palestine was to help both Syria and Lebanon gain their independence at French expense. With significant British assistance the Lebanese did so in 1943. The French found out that the British were plotting with the Syrians to the same end the following year.’ (3)

‘The British needed to allow the Free French to lead a takeover of Syria to avoid the impression that they were trying to usurp the French… When this welter of disturbing information reached London, Churchill asked his debonair foreign secretary Anthony Eden for an urgent review of British policy towards the Arab world. On 27 May [1940] Eden circulated a short but crucial memorandum to his cabinet colleagues. In it he admitted that the root cause of Arab dissatisfaction was “the Palestine problem”, but argued that it might most easily be assuaged by a British promise that the Syrians and Lebanese would have their independence, if the Free French refused to offer such a guarantee, or, having offered it, it failed to work … The British government had just committed itself to pursuing a policy of support for Lebanese and Syrian independence designed to defuse Arab anger cause by their rule in Palestine.’ (213-4)

‘The collapse of French influence in Syria [in 1945] was immediate and total… The British and French hammered out a deal to leave [Lebanon and Syria] simultaneously – “This should end French intrigues in Palestine,” the foreign secretary note optimistically – and both sides’ troops withdrew from Syria in April 1946, and from the Lebanon that August. After twenty-six years, the French mandate in the Middle East was over.

‘The loss of Lebanon and Syria paved the way for a new, pro-Zionist French policy…’ (309)

France supported Jewish terrorism in Palestine before and after the establishment of Israel in 1948 as a way of taking revenge on Britain for the way it had undermined French rule in Syria and Lebanon.

‘… while the British were fighting and dying to liberate France, their supposed allies the French were secretly backing Jewish efforts to kill British soldiers and officials in Palestine.’ (1)

(Concerning the Jewish underground’s need for weapons to fight the British in Palestine in (1944). ‘The answer, the Stern Gang decided, was to appeal to the French for help. It hoped that the French, having been so recently humiliated by the British in the Lebanon, might make common cause against the enemy they shared.’ (271)

(Describing a meeting in August 1945 between Tuvia Arazi, representing the Haganah, and Francois Coulet, representing the French foreign ministry.) ‘Recalling a speech that Spears [the British Representative in Beirut] had made a few months earlier, in which the British politician had said that France and the Zionists were the main hindrances to British Middle Eastern policy, Arazi suggested [to Coulet] that there was a more positive basis than a shared dislike of Britain for an alliance between the two. All that was required was for France to rethink its foreign policy. For compared to the widespread hatred that France now evoked across the Arab Middle East, he said, there were coherent Zionist organisations that recognised France’s rightful place in the world, and hoped that the French would assume it once again.

‘Although De Gaulle had no great sympathy for the Jews, he had not forgotten the June “insult” [Britain’s actions against the French in Lebanon and Syria] and could immediately see how the Zionists might be useful in avenging it. When he met the French representative of the Zionist movement, Marc Jarblum, in Paris later in the year, he mused that “the Jews in Palestine are the only ones who can chase the British out of the Middle East.”

‘… In what the Zionists were proposing … France could use the Zionists not just to give the British a bloody nose in Palestine, but to defeat the Arab League, which has made Palestine its cause celebre …

‘On 10 November, Bidault quietly told David Ben-Gurion that France would support the Zionists’ cause …’ (310-311)

(Concerning a secret deal in May 1945 for France to supply weapons to the Irgun.) ‘At the end of May he reached a secret deal with Ariel. France would supply 153 million francs’ worth of weaponry, in exchange for influence in the newly independent Jewish state. The arms were delivered to Ariel … in early June and shipped to Tel Aviv aboard a landing craft the Irgun had purchased, the Altalena. Although the Altalena was sunk on Ben-Gurion’s orders off Tel Aviv to prevent the Irgun becoming too powerful, the transaction marked the beginning of a sustained relationship: France would be Israel’s leading arms supplier until 1956.’ (364)

‘What makes this venomous rivalry between Britain and France so important is that it fuelled today’s Arab-Israeli conflict. Britain’s use of the Zionists to thwart French ambition in the Middle East led to a dramatic escalation in tensions between the Arabs and the Jews. But it was the French who played a vital part in the creation of the state of Israel, by helping the Jews organise the large-scale immigration and devastating terrorism that finally engulfed the bankrupt British mandate in 1948.’ (4)

James Barr ties together the main themes of the book at the end of the final chapter entitled ‘A Settling of Scores’.

(The attempted assassination in Damascus in 1948 of W.F. Stirling, who had been a British agent in Syria, was probably instigated by the French, since it was described by the French charge d’affaires in Damascus at the time as ‘the result of a settling of scores.’)

‘The departure of W.F. Stirling to Cairo [after the attempted assassination] marked the end of a thirty-year-long last gasp of empire that aggravated the conflict that remains unsolved today. It was the struggle between Britain and France for the mastery of the Middle East that led the two countries to carve up the Ottoman Empire with the Sykes-Picot agreement, and it was British dissatisfaction over the outcomes of this deal that led them, fatefully, to proclaim their support for Zionist ambitions in the Balfour Declaration. And so the Jews’ right to a country of their own became dangerously associated with a cynical imperial manoeuvre that was originally designed to outwit the French.

‘The Balfour Declaration was an acknowledgement of the fact that the zenith of empire had now passed. Frontiers like Sykes’s “drawn with a stroke of a pencil across a map of the world”, according to one of his contemporaries – which had seemed so assured when they were used to divide up Africa in the nineteenth century, looked arrogant when applied to the Ottoman Empire in the twentieth. It was the flimsiness of their entitlement to redraw the political map of the Middle East that explained why the British now had to use a commitment to a stateless people to camouflage their determination to take over Palestine. When the French realised the depth of Arab opposition to their rule they quickly followed suit, hiving off the Lebanon in supposed deference to the wishes of the Christian community there.

‘Britain’s sponsorship of the Jews in Palestine and France’s favouritism of the Christians in the Lebanon were policies designed to strengthen their respective positions by eliciting gratitude from both minorities. The appreciation they generated by doing so was short-lived, but they deeply antagonised the predominantly Muslim Arab populations of both countries, and the wider region, with irreversible effects. As Britain and France became increasingly unpopular, they were forced into oscillating alliances that only polarised Arab and Jew, Christian and Muslim further. The mandatories’ abrupt changes of policy under pressure, and their refusal to institute meaningful, representative government, made it clear to those they ruled that violence worked.

‘Until the Second World War the British reluctantly accepted the presence of the French as what their ambassador to Cairo, Lord Killearn, termed “an unnecessary evil which we must make the best of”. While a further war with Germany looked possible, then likely, and finally inevitable, Britain’s relations with metropolitan France were more important. “The plain fact was that the presence of the French in the Levant States was a perpetual irritant which upset British policy in the Middle East,” Killearn acknowledged, “but I had always realised that we ought to conform and adapt our local policy to the needs of our higher interests in regard to metropolitan France which was our neighbour just across the channel.”

‘The collapse of France in 1940 destroyed the assumption on which this policy was based – that France would be a vital ally in any fight with Germany. The vacuum gave British officials the opportunity to press for the independence of Syria and Lebanon, to provide the Arabs with the representative government they were still unwilling to supply in Palestine. This effort at distraction briefly worked, but ultimately its consequences made it self-defeating. As onlookers immediately recognised, Lebanese and Syrian independence set a precedent in the countries immediately to the south, and it was not long before the British were ousted there too.

‘The wrangling between Britain and the Free French throughout the war years had a further, far-reaching consequence when de Gaulle returned to power in 1958. As president of France it was he who infamously vetoed Harold Macmillan’s application to join the Common Market. In tracing exactly why de Gaulle said Non, it is, surprisingly, to the hot and dusty cities of Beirut and Damascus that we should look. The general’s experience of British machinations in both place s profoundly shaped his reluctance to allow his wartime rivals to join his European club. It is a tale from which neither country emerges with much credit.’ (375-7)

s profoundly shaped his reluctance to allow his wartime rivals to join his European club. It is a tale from which neither country emerges with much credit.’ (375-7)

Colin Chapman

23 May, 2017